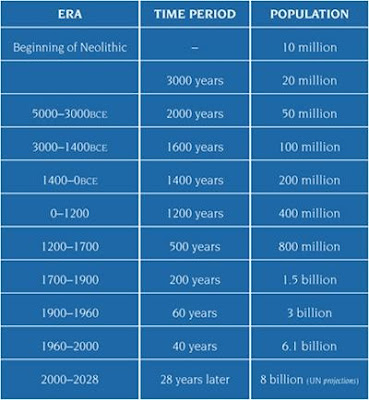

In the year 2000 the human inhabitants of Earth reached 6 billion. Now, in 2003, there are 6.1 billion of us. And not only is the world population increasing, the rate at which it is growing has also been increasing. The above table illustrates this, including the great acceleration over the past 200 years. It forces us to ask the sustainability question: What will happen if the human population continues on its current growth path?

Growing populations are faced with the harsh reality of limited natural resources. The issue of water supply is a good example to demonstrate that unrestrained population growth is not sustainable. Consider this:

1. Water, like other natural resources, is not evenly distributed around the globe. The countries described as ‘developed’ or ‘industrialised’ have in general more abundant sources of water, or the technology to use water more efficiently.

2. The supply of fresh water is essentially fixed. While technical means are being explored to increase the supply of fresh water (such as Desalination) their impact is likely to be limited.

3. We are already consuming close to the planet’s limits. Worldwide, 54% of the annual available fresh water is already being used. This may seem to leave a lot to spare, but scientists have demonstrated that we need to leave a certain volume of water in rivers and other wetlands as an ecological ‘reserve’, in order to maintain their functional viability. When we use up this reserve, we destroy these ecosystems and reduce the overall available volume of water.

4. This level of use (54%) is based on unequal consumption: Around the world, some 1.1 billion people do not have access to fresh water, or consume less than the basic daily requirement

of 50 litres.

5. Population growth will also result in greater volumes of pollution. In developing countries, 90–95% of sewage and 70% of industrial waste are dumped into surface waters thus polluting the water supply. Water quality is also affected by chemical run-off from pesticides and fertilisers and acid rain from air pollution, requiring expensive, energy-intensive processes to clean it for human use. In a recent case in Brits, residents could not use council water because of pollution in the Hartbeespoort Dam. Pollution clearly decreases the volume (and increases the cost) of available water.

A child born today in an industrialised country will consume more and pollute more in his or her lifetime than 30 to 50 children born in a developing country.

In 2000, 508 million people lived in 31 water-stressed or waterscarce countries. By the year 2050, this will have rocketed to 4.2 billion people living in countries that cannot meet the minimum requirement of 50 litres of water a day.

Water is not only a basic human need, without which we die. It is also the basis of health, food security and economic development. For individual families, lack of access to clean water is associated with unhygienic living conditions, already one of the biggest causes of deaths among infants. On a national and regional level, cash crops and other industries depend on water supplies. As water becomes scarcer, we see not only a decrease in the quality of life, but an increase in social conflict.

The same scenario will play out (and already does) for land and other non-renewable natural resources. These resources limit the number of people the earth can bear sustainably. This is why the rate at which the world population is growing, is such a serious ecological and social threat.

Just as the world’s natural resources are unequally distributed, the world population is also unequally distributed. High population numbers are associated with those regions where natural resources are generally more limited. Here the population increase is also the fastest, the consumption per person the lowest, and the negative impacts of growth most acutely felt.

At the current global population growth rate of 1.3%, there are 77 million more people living on this planet per year. Six countries alone are responsible for half of this growth: India (for 21%), China, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and Indonesia.

There has been a general decline in fertility in countries described as ‘developing’ (to an average of just under three children per woman – half of the 1969 figures), and the figure is expected to decrease further to 2.17 by 2045–2050.

But despite this trend, most of the projected growth in the world population will take place in developing countries. By 2050, 85% of the world population will be living in developing countries. (The comparative figure for industrialised countries is 1.6 children per woman.) The 49 ‘least-developed’ countries will almost triple in size. This level of growth will almost certainly have devastating effects for their environment and inhabitants, with rippling impacts on their neighbours and other countries to which people may migrate.

One of the effects of population growth can be seen in cities. As rural environments become less able to sustain people, an estimated 160 000 rural dwellers move to cities every day. This results in sprawling, densely populated urban areas under great social, economic and environmental stress.

City surroundings are depleted through concentrated extraction of resources ranging from water to firewood; the conversion of farmland or wetlands for housing, roads and shopping centres; and the spill-over of pollution, which is often worsened by local governments failing to provide the necessary facilities for the swelling numbers.

Do we have a problem in South Africa? Our population growth rate is slowing down – from 2.1% in 1975–2000, to a predicted 0.2% for 2000–2015. This figure takes deaths due to HIV/Aids into account. While HIV/Aids slows the growth rate (it would probably have been 1.4% in 2010 without HIV/Aids), the epidemic will probably not result in negative population growth (a smaller population). In 2000, our population was 43.3 million.

Is this a problem? Are there too many of us? For answers, we need to look towards the environmental resources, which must sustain us. In each locality, we need to consider whether that particular environment is able to support the people living in it. And critically, we need to ask whether current needs are being met adequately.

Our apartheid history has much to do with how the population has been distributed, and associated environmental degradation. In former Bantustan areas like KwaMhlanga and Transkei, too many people were forced to live in resource-poor areas with limited capacity to support their artificially high numbers. The effects on both the environment and people’s ability to sustain a livelihood were devastating. Looking for alternative livelihoods, many rural South Africans moved to cities, where the majority of us (56.9%) now live. Here informal settlements are expanding, often into sensitive or high-risk areas such as flood plains or waste dumps. Lacking resources, they contribute to environmental and health issues, e.g. pollution of ground water through untreated sewage. Local governments struggle to meet the demand for housing, water, sanitation, waste removal, transport and health services. Biodiversity is lost as remnants of indigenous vegetation are destroyed. Considering that the economic and ecological demands of our existing population are already straining the Earth’s capacity, and that many basic human needs are not yet met, can we afford to continue growing in numbers?

If we want to achieve a sustainable relationship between natural resources, development and human numbers, we need to consider the fact that many people still do not get a big enough slice of the cake, as well as the reality that the Earth’s cake is of a limited size. As we saw from the water example, natural resources are essentially fixed, and taking strain under the demands of consumption and growing populations.

Yes, we can produce more food and we should distribute resources more fairly and efficiently around the globe. This, along with reducing over-consumption and discarding discriminatory economics, can alleviate a great deal of hunger and hardship (see Topic ECONOMICS). Technological advances towards energyefficient and resource-light production can reduce resource use and pollution, but these steps will not reverse the impact of the population explosion. Something must be done to slow down population growth – but what?

The greatest threat to sustainable development is consumption; consumption is linked to unsustainable production and overconsumption among the consumer classes in both the north and south, and to population growth, particularly in the south. Different camps fight about who has the greater environmental impact – the rich over-consumers or the poor populationgrowers. The fight may just defer responsibility, however, because BOTH over-consumption and over-population must be addressed, if we are to achieve ecological sustainability and social justice – and we cannot deal with them as separate issues. The answer is not as simple as ‘family planning’ or reducing the number of pregnancies. We need to understand what will make family planning and fertility control possible and likely, from a social point of view, and how these factors can be addressed.

Most agencies involved in population development advocate a multi-faceted and integrated approach. They point out that high population growth rates are associated with poverty, environmental degradation, limited opportunities and unequal power relations. High fertility is still a feature of rural life in many areas, even when the rationale for having large families (needing many hands for harvesting, for example) are no longer valid.

In these situations women often do not have the power to choose the size and spacing of their family. Addressing these vicious cycles requires an integrated approach, in which family planning goes hand in hand with increasing women’s rights and their ability to exercise them, reducing poverty, protecting the environment and increasing livelihood options. These goals are all interrelated and cannot be separated from economic models and over-consumption (see Topic Poverty Alleviation).

2. Legal and community protection against sexual harassment and violence.

3. Education (in many parts of the world it is still unusual for girls to be educated).

4. Establishing women’s right to own land (many women farm without the ability to make decisions about the management of the land).

5. Reproductive health care (UN agencies lack funds to provide fertility control to all the people requiring it).

6. Adequate general health and social support, so that each child born can be treated with the necessary care and respect.

7. Reducing social strife and conflict so that life is no longer treated as ‘cheap’ anywhere on Earth.